How to Read More in Japanese – I Tried Reading in Japanese Every Day for a Month

/Every new year for about four years in a row, I have resolved to “read more”.

…and every year on about January 8th, I realise I have forgotten, and give up.

Have you heard of the S.M.A.R.T. acronym for setting “good goals"? SMART goals are objectives that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timely.

Looking at the SMART criteria, it’s fairly obvious that “read more” is not a good goal, because it’s not remotely specific or measurable. Let’s say you resolve to read every day. How much reading do you have to do for it to count?

With this in mind, I decided to spend a month reading in Japanese every day. I’d read for 20 minutes every day in May, and track my progress on instagram stories.

Tip 1: Look at your reading goals. Are they Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timely? If not, they might need tweaking.

I chose 20 minutes because as well as being specific and measurable, I thought it was achievable – perhaps not do-able every day forever, for me, but certainly every day for a month.

Reading more in Japanese is a super-relevant goal for me, as I want to practice Japanese, and also just have fun reading.

And it was timely, as I’m running my Tadoku reading course again this summer and wanted to make sure I was practising what I preach with regards to extensive reading.

I decided to read according to Tadoku principles. Tadoku (多読) literally means “read-a-lot” and is a method of reading easy, fun books to learn a foreign language. It’s sometimes called “extensive reading”.

The four golden rules of Tadoku (from NPO Tadoku Supporters) are:

Four Golden Rules:

1. Start from scratch.

Read easy books you can enjoy without translating. That way, you will understand better and so you will read more.

2. Don’t use your dictionary

Don’t use your dictionary when you come across words you don’t know. Guess the meaning from the pictures and/or the story.

3. Skip over difficult words, phrases and passages.

If guessing doesn’t work, skip over that word, phrase or passage and go on reading. You can often enjoy the book without understanding every small detail.

4. When the going gets tough, quit the book and pick up another.

The going gets tough when the book is not suitable for your level or your interest. Simply throw the book away and start reading something else.

I decided to read at lunchtime on days when that fits my schedule, or the evenings when I’m not teaching.

Tip 2: Decide in advance what the best times are for you to read. Is the morning best for you, or the evening? If you want to squeeze 10 or 20 minutes of activity into your day, you might need to plan it in a bit.

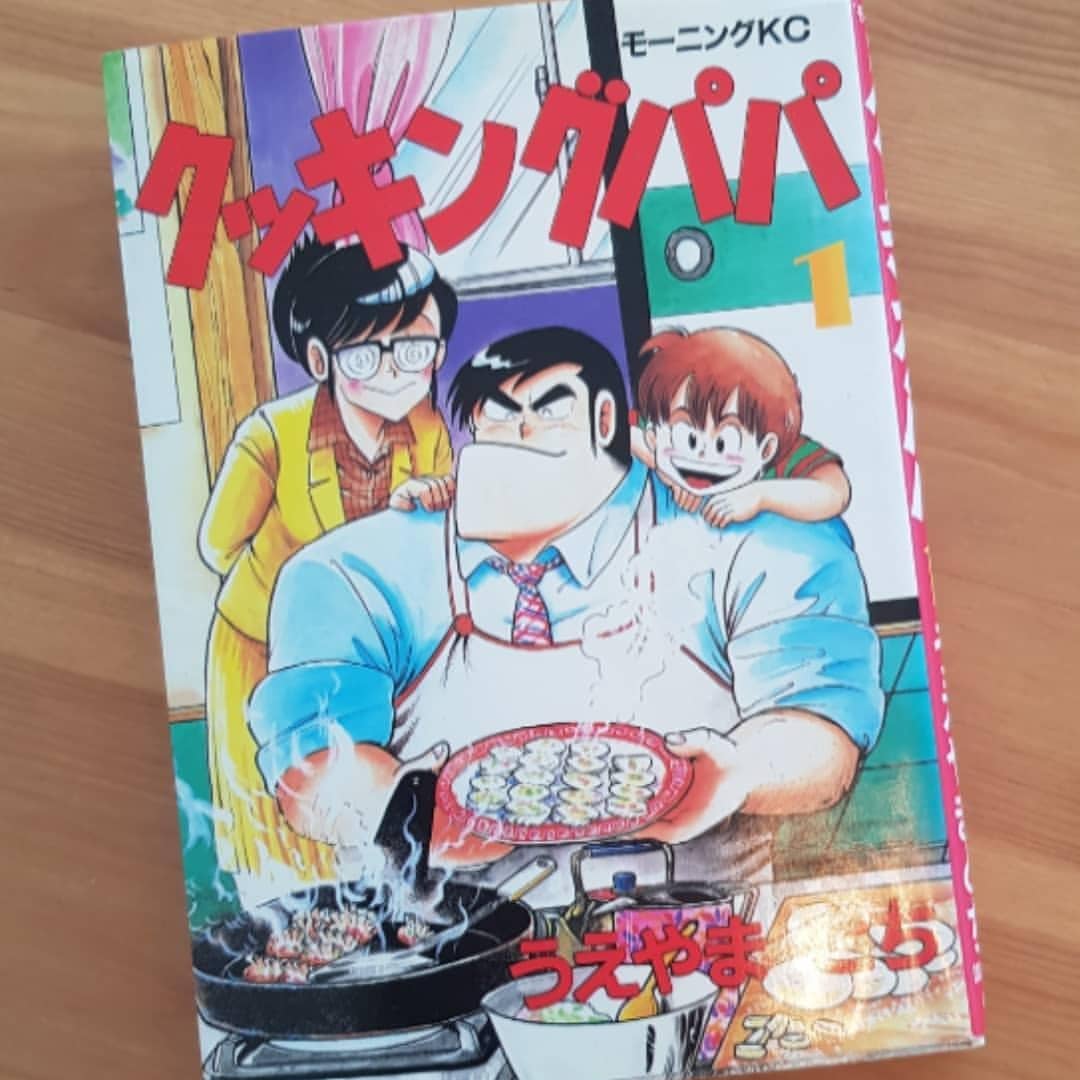

I started by reading a manga that had been sitting on my shelf unread for (ahem) three years - Cooking Papa (クッキングパパ) . It’s a seinen manga (青年漫画, books primarily marketed towards young adult men), and I was reasonably sure it would be easy for me.

Tip 3: Read easy books. That way, you will understand better, and so you will read more.

Cooking Papa is a 1985 manga about a Japanese salaryman who is a talented home cook. I had a lot of fun reading this book, and it was a really easy way into reading every day. It did make me very hungry though…

There were some words I didn’t know in the recipe section, but remembering Tadoku Rule 2 (don’t use your dictionary!) I skipped over them and kept reading.

Tip 4: Don't use your dictionary when you come across words you don’t know. Guess the meaning from pictures or from context.

Next up I decided to finish a book I started last summer, 日本語教師のための多読授業入門 (nihongo kyoushi no tame no tadoku jugyou nyuumon, “An Introduction to Tadoku Instruction for Teachers of Japanese”).

It’s all about how to do Tadoku, and I read it using Tadoku principles. META.

At the end of the book I discovered an amazing resource - a list of picture books and manga for tadoku students, ordered by difficulty. This was incredibly useful, and I used the list to order some new books for my students. I’m so pleased I finished this book!

Next up I switched back to fiction, with Gaku (岳, literally “peak”), another seinen manga, all about a mountain rescue team. I really enjoyed this book, and was pleased to have polished off another manga that had been sitting on my bookshelf unread for a while.

Tip 5: Consider switching between fiction and non-fiction to broaden your reading and keep things interesting.

After Gaku, I decided to read some long-form fiction, by attempting to finish the first Harry Potter book in Japanese.

Technically, I have been reading this book for about eight years, principally because I only ever read it on planes for some reason, but more importantly because I started reading it when it was too hard for me. Big mistake.

When I first started “reading” Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in Japanese, back in 2011, I had never read a book in Japanese before. It was really hard, and I looked up a lot of words as I went along.

I remember that words like マント manto, cloak, and 杖 tsue, wand, weren’t in my beginner dictionary, so it was a very frustrating experience.

I can see that looking up a large number of words slowed me down a lot.

I can also see now that the book was just too hard for me then. If I’d read easy books instead, I probably could have read hundreds of books in that time, but instead I laboured through Philosopher’s Stone, taking it on trains and planes with me and forcing myself to read one or two pages every year or so.

Anyway, I started reading it again this month, and I finished it!

(That means it took me eight years or so to read the first three-quarters of the book, and 7 days to read the rest of it.)

….that doesn’t mean I understood every word though.

Tip 6: Skip over difficult words, phrases and passages. If guessing doesn’t work, skip over that word, phrase or passage and go on reading. You can often enjoy the book without understanding every small detail.

Words I tend not to know in Harry Potter are usually adverbs describing how something is said.

Take a look at these (made-up) examples:

“We could be killed, or worse, expelled!” said Hermione somethingly.

“Ah, shut up, Dursley, yeh great prune.” Hagrid somethinged.

“The truth," Dumbledore said somethingly, "is a beautiful and terrible thing.”

I bet you can more or less guess what the ‘something’s are in those sentences, right? If a book is the right level for you, you can confidently skip over words you don’t know and still understand from context what is going on.

I enjoyed the book, and I was very happy to have finally finished it.

Tip 7: read translations of stories you’ve already read. Because you know the story, it’s easier to follow.

On Day 27 of the month, I started Norwegian Wood (ノルウェイの森 Noruwei no Mori).

Time for another confession: this book is actually a really big part of the reason I started learning Japanese. When I was at university, I was pretty big into Haruki Murakami, and I decided I was going to read his books in Japanese one day.

I’ve read Norwegian Wood in English, but I couldn’t read the book when I bought it in 2011, the year I moved to Japan. I tried, much in the same way as I tried with Harry Potter. I looked up words and stuck post-its on the pages, but the book was too hard then for me to enjoy reading. So it sat on the shelf until this month, when I decided to give it another go.

Norwegian Wood is a good level for me to be reading now, but I didn’t get very far through before it was the last day of my month-long challenge. I did like the book, and I thought I’d keep reading it after the month was over, but I didn’t. So inadvertently, I practiced rule four of tadoku:

Tip 8: When you’re not interested in a book any more, stop reading it, and start reading something else.

On last year’s Tadoku course, my students found this the most difficult rule to follow. But from the Introduction to Tadoku book, I’d learned that having the courage to stop reading a book, without feeling guilty, is one of the most powerful lessons we can learn from extensive reading.

So Norwegian Wood is back on my shelf, still unfinished. Maybe I’ll read it another time. Or maybe I’ll just read something else?

Like many people in the UK, I studied French in school. I liked French. I thought it was really fun to speak another language, to talk with people, and to try and listen to what was going on in a new country. (Still do!)

When I was 14 we went on a school exchange to the city of Reims, in northeastern France. I was paired with a boy, which I’m sure some 14-year-olds would find very exciting but which I found unbearably awkward. He was very sweet and we completely ignored each other.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and I didn’t learn or use any more French until, at some point in lockdown, I decided on a whim to take some one-to-one lessons with online teachers. Here are some things I learned about French, about language learning, and about myself.